The part played by indigenous Australians in our military history is likely to be one of the themes of the combined Marist JPICC event in 2015. 'Black Diggers' helps us set the scene...

Black Diggers Reviewed

Sandra Phillips

Sandra Roberts is Lecturer, Creative Writing and Literary Studies, School of Media, Entertainment and Creative Arts, Creative Industries Faculty at Queensland University of Technology

| Black Diggers brings black and white Australians into the same narrative. Branco Gaica/Brisbane Festival.

The performance space in which Wesley Enoch’s play Black Diggers is being performed at the Brisbane Festival is a large black box.

It features a raised stage in the middle which proves versatile for battlegrounds at home and abroad – and later as ground for discriminatory encounters experienced by Aboriginal returned ex-servicemen.

The fire-filled 44-gallon drum off to the side creates another space of encounter; there are few other props. Now and then, dates and other details are whitewashed on the black walls.

As the show unfolds, the ensemble adds layers to these painted stories. Actor and ex-serviceman George Bostock, recognisable elder statesman in the Aboriginal world, methodically shines a pair of shoes as the younger men range around.

It’s a gentle opening to a story of stark extremes that remembers the Aboriginal men who served the British Commonwealth in the first world war, overcoming barriers to enlist, experiencing typical hardships of battle, and returning changed to a nation that hadn’t.

Well-funded to coincide with Australia’s 100 Years of Anzac commemorations, Black Diggers has the main stage and dominant discourse to work with.

It also has the challenge of working against entrenched mythology that preserves sacrifice and nation-building as white virtues.

Telling the story of 100 years in a hundred minutes is an enormous task – complicated further when the play rewinds to the 19th century to illuminate effects of land battles fought on this continent’s soil.

Cue the cry of a baby that has survived a settler massacre. If the cry is to humanise and give “voice” to innocent flesh and bone it achieves its goal.

One settler wants to bludgeon to death this “remnant” of a forever-disrupted Aboriginal world, another wants to simply “leave it for the dogs”.

The “Professor” appears, asserts his authority and, perhaps motivated by scientific curiosity, saves the “picaninny” and goes on to raise him as his own.

In a later scene, actor Luke Carroll convinces us he is that baby.

Old enough for language, but not yet old enough to understand, he asks what happened to his parents.

Awkwardness ensues. The “baby” knows enough to feel something bad has been done to his parents and anxiously cries out: “Were they frightened?”

We have been warned, of course, that this is no straightforward Anzac re-telling replete with khaki-swaddled jingoisms and jaunty slouch hats.

Black Diggers enters the contemporary battle of ideas armed with the research it needs. After all, getting creative with national mythology is dangerous business.

The story moves from our frontier to those of the first world war. In the trenches the diggers’ banter shows strong

[top of next column...] |

camaraderie and palpable fear. Bombs hail down nearby — the sound and light symphony not unlike that of a tropical thunderstorm.

The lighting design is exceptional throughout. Several scenes of direct action are foregrounded: hand-to-hand combat leads to death.

The close-range shooting of four German soldiers is accompanied by a throwaway line confirming that one of the four was in the process of pulling out a weapon.

We are thus encouraged to accept these killings as morally justified.

Occasionally Black Diggers tells us what is happening rather than showing us – but this is perhaps inevitable given the gaps in our mainstream and shared history knowledge bases.

The exposition gives voice to the research, often in the form of monologues.

This includes an early geopolitical take on the countries and events leading to the first world war styled in the Horrible Histories genre.

Facts are delivered fast – and later we watch a spotlit serviceman holding his glass and speaking through raw emotion of his experience at war and his return home.

In perhaps the most controversial line of the play, he implores: “I am Australian”.

Enoch’s direction doesn’t leave anyone behind. The ensemble is strong and each member appears to make each other stronger.

Carroll is a standout, so too is David Page. All are versatile. The actors change character and identities – from black to white to south Asian and back again; they are aged as infants, teens, young adults, middle-aged, and geriatric.

There’s even a case of gender change effected through the donning of an apron and cardigan, as well as acting informed by a young man who may have had a mum and aunties to draw inspiration from.

The all-male ensemble, largely costumed in khaki, avoids an over-played machismo.

There is a sensitivity and empathy here alongside the accoutrement and collateral of war: these are real men with real emotions with real thoughts and real challenges and relationships.

Through Black Diggers, Enoch and his creative team do what Australia’s best paid minds can’t — bring black and white Australia into the one narrative with some plausibility while not resiling from what has been euphemistically called “blemishes on our history”.

Being Australian may not be a goal of all Indigenous Peoples in Australia, but recognising and atoning for the brutality of our colonial histories is perhaps one way for our Peoples to think the nation can begin to know us and our stories.

[Black Diggers played at the Brisbane Festival Sep 24-Oct 12]

Posted: Nov 20, 2014 |

|

Faith in Action: 'Be the change'

Co-sponsored by Sydney Archdiocese's Justice & Peace office and Catholic Youtuh Services, this 'Social Justice Expo' will attract young adults to the Broadway, Sydney, campus of Notre Dame University over the weekend of Nov 03-05.

For details: click here

[Posted Oct 20] |

|

Migrants and Refugee conference

Marists were amongst those gathered for the National conference on the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees at ACU's North Sydney campus this week.

Topics included climate-induced migration, human trafficking, asylum seekers, international students and a range of other areas of pastoral concern.

[Posted

Oct 02] |

| Above: Prof Maya Cranich's presentation on ACU's online program on the Thai-Burma border | Maya Cranich and Immigration lawyer, David Manne Below: Catholic Mission-sponsored Village Space drama | Fr Jim Carty SM / young author on Nauru detention, Mark Isaacs |

|

First World Day against Traffickng in Persons

Each year millions of children, women and men from all regions of the world are trafficked, their hope is stolen.

To mark the first ever United Nations World Day against Trafficking in Persons, Jul 30, people across the globe are encouraged to symbolically help give back this precious item.

[Posted

Jul 30] |

|

100th World Day of Migrants and Refugees

[Posted

Jul 25] |

The Society of Mary has a long involvement with refugees.

Below: Newly-arrived Karenni (Burmese) families in Australia | Refugees in Mae La camp, Thailand |

|

ACMRO: review Manus Is detention

The Australian Catholic Migrant and Refugee Office (ACMRO) is calling on the Australian Government to reconsider its policy of resettling refugees on Manus Island.

Full text of May 27 press release: click here

[Posted

May 29] |

Bishop Eugene Hurley / Bishop Christopher Saunders |

Prof Neil Ormerod / Kerry Murphy |

Asylum Seekers: Bishops' statement and commentaries

Click below for three recent and important articles on Australia's present attitude towards those seeking asylum in our country....

[Posted May 23] |

|

Refugee Council May bulletin

In easily-readable summary format, RCOA offers a wide range of topical issues concerning refugees and asylum seekers. Important reading. Click here

[Posted May 21] |

SIEV 221 memories - continued

'The dot on the map

is bigger than the island'

Returning from Easter on Christmas Island, Fr Jim Carty finishes the story of SIEV 221

[See below]

| I have returned to Sydney with a sense of futility, guilt and anger in the knowledge that the people I met, talked, shared and prayed with remain in what is often referred to as the corrosive cloud of uncertainty and fear- as a direct result of the "turn back the boats' whatever the cost either human or economic.

Many refer to them as being "in limbo" a concept that no longer has any theological credence.

However I think their reality is more akin to Dante’s "vestibule of hell" such is the policy of the current Government and the previous one.

The majority of those in detention in the four camp sites on the Island arrived after the Jul 19, 2013, the date on which the new policy of exclusion of any boat arrivals from ever being accepted for settlement in Australia was introduced, whether or not they are found to be genuine refugees under the UN Convention.

Their options: possible settlement in Nauru, Manus Island, or now we are told, Cambodia; or returning to their homeland and for most returning to danger including imprisonment, torture or death

But before telling you the stories of some of those I met I will complete the story of SIEV 221 that I started in my last blog. (The last paragraph: The fate of SIEV 221: you probably won't remember the name but you will remember the tragic event that happened just of the ragged rocky shore of Christmas Island. I will return to this story tomorrow).

The SIEV 221 as shown in one of the photos has a dedication a few meters from the SIEV X memorial.

Once again it is a solemn reminder of the desperation of some who seek a safe and peaceful haven from persecution or war.

I must add that not all who arrive necessarily fulfil the definition of an asylum seeker according to the UN Convention and can legitimately be denied resettlement in Australia, but that does not justify treating all who arrive by boat as so called "illegals" with punitive isolation as a deterrent to others who may attempt to follow- punishing the innocent does not justify cruel and inhuman means and make no mistake that is what is happening out of sight and mind but in our name.

What we are doing is a form of reprisal- make those who come suffer to deter others- the depression and mental suffering we inflict on them is

unconscionable especially on the children

But I digress. The memorial recalls that early on Wednesday 15th December the SIEV 221 having eluded the Australian Patrol boats approached the Eastern side of the Island not far from Flying Fish Cove the only safe harbour but only in calm weather.

The storm that had raged most of the night had not abated as the helmsman of the fragile vessel looked desperately for a place to land.

[top of next column...] |

As the boat chugged parallel and closer to the shore a wave hit broadside swamping the engine.

Without power it was at the mercy of the violent elements and began to break up throwing many into the rolling waters, others desperately clung to what remained of the boat above the waves.

When news of the disaster spread around the island, many members of the community hastened to the site to offer what help they could and watched in anguish and frustration as bodies were being flung about in the waves- they were able to save some even as others were thrown lifeless on the flesh tearing, bone cracking deeply fissured volcanic razor sharp cliffs.

One witness with whom I spoke related seeing the body of a baby dumped on the cliff- perhaps it was the three month old baby whose name appears on one of the 51 white stones surrounding the memorial representing the total number of lives lost from the SIEV 221

The gallant actions of Naval personnel who risked their lives to save as many as they could in terrible conditions and at real risk to their own lives should not be forgotten.

It’s timely to remember that the decision to build Detention facilities was taken by the Australian Government with little or no consultation with the local community.

Over time the initial Army tent facilities that made up the first camp developed into what is now there: four separate camps the largest being the one at North West Point but according to plans designed, I am told, by the architect of the high security detention centre at Guantanamo Bay. It works with the same efficiency.

I mention this because the community has been traumatised by the SIEV 221 experience- the local community of about 1450 many of Malay decent, with very sensitive beliefs around death and its causes.

I will conclude this blog now with the promise of two or three more stories, but not necessarily joyful ones- of some of those locked up in the camps, why they fled and their dreams.

Epilogue: The 51 who died placed an impossible burden on the morgue facilities on the Island- while decisions were considered in Canberra as to what to do they, the deceased, they were kept just outside the Hospital in refrigerated containers for more than three weeks.

Five, four adults and one child, all Christian were brought to Australia for burial - I was able to attend the funeral- a profoundly sad and moving experience to see five family survivors struggle to comprehend.

Jim

Posted: May 07, 2014 |

Fr Jim's Easter at Christmas Island

'The dot on the map

is bigger than the island'

SIEV X and other stories

from Fr Jim Carty SM's blogs

| Christmas Island, Easter 2014

I left Perth on Apr 10 on a Virgin flight, the fare paid for by the Department of Immigration and Boarder Protection.

Does that make me guilty of collusion in what is a brutal devastating policy of locking the boat people up with little or no hope of a humane outcome of those who have genuine claims to asylum?

You will notice the change in the name of the Ministry; it seems each new Government feels compelled to make its mark by changing the name.

Howard changed the name to ‘Department of Immigration and Citizenship’ and quickly notified all that the "A" should be included in the acronym to read: DIAC!

After all as the head of Government he didn't want to be known as head of that department - it wouldn't look good on his CV.

The latest change defies a sensible pronunciation: DIBP.

But the significance of the change is obvious. And the Government Printers are once again the winners.

Sister Margaret Sheppard, a Parramatta Mercy, is here on three month pastoral care program. She has just finished three months in Curtin.

She is an engaging extrovert and her past and vast teaching experience and as principal of schools offer much to all, detainees and staff even for an ageing homilist by providing the word he struggles to recall.

She fills the silence in many places and often. The detainees look forward to her visits and conversations.

As a guide for myself I will list the main stories or issues as dot points here and work my way down the list in the next few days or when I return to Sydney

~ Easter on Christmas Island with the community and in the detention centres

~SIEV X

~ SIEV 221

~ The Coolie: slave? Or Indentured labourer?

~ Reflections on the situation prevailing here- the tangible sadness and grief with not knowing when where or how

~ The special issue of children on detention

SIEV X

So out of order let’s begin with the SIEV X (Suspicious Illegal Entry Vessel, number 10).

You will recall that this doomed hulk sank with the loss of 353 persons - 146 were children 143 women and 65 men a rare gender cross section directly attributed to the TPV policy introduced by the Howard Government which denied family reunion to those adjudged genuine refugees but with the potential of being returned to their home land if peace descended- most were from Iraq and Afghanistan!

The day of the disaster

There were many men fathers and husband of families who remained in dangerous circumstance either at home or in the case of Afghans in the dangerous Pakistan city of Quetta.

After three, four, five, even six years of waiting the separated families could wait no longer and set out to be reunited.

The SIEV X was old and shonky infrastructure was added to accommodate more people.

Over 400 were crowded on to the boat with coercion and it set off on it's doomed voyage.

Tony Kevin wrote an important book on this disaster entitled "A Certain Maritime Incident". Worth reading.

[top of next column...] |

I write in haste and with difficulty - the access to the internet and wifi is difficult and problematic.

So I will finish here so that at least one blog will be sent from the island with more blogs and photos to follow from home.

With very warm and muggy regards

Jim

-----------

Apr 24

I travelled to Perth late this afternoon then spent Anzac Day attending a morning service and Mass at the local Church with my host Robin and her family dear friends from my Geelong days (1967).

Returning to the SIEV X.

Soon after departing Indonesian waters the overcrowded boat started taking on water.

On board were 23 Sabian Mandaean- members of a small ancient sect with links to John the Baptist, found mostly in Iran and Iraq and with a sad history of violent persecution.(more about them in a another blog).

By chance a small Indonesian fishing boat came along side- the Mandaeans were put off onto the boat- the SIEV X continued on its fateful journey sinking some hours later.

The fishing vessel made it safely back to Indonesia.

News of the disaster was accompanied by a heart rending photo of three young sisters aged about 4,5 and 6, dressed in their Sunday best and taken just before they boarded the boat with their mother in eager anticipation of meeting their father in Australia.

Their bodies were never found, like so many others the sea claimed that night.

Memorials to SIEV X and SIEV 221

The fate of SIEV 221

You probably won't remember the name but you will remember this other tragic event that happened just of the ragged rocky shore of Christmas Island. I will return to this story later…

Jim

Posted: Apr 26, 2014

Sunset on Christmas Island

|

|

New: US province JPIC web page

The U.S. Marist province website has been enhanced this month with a feature page on Justice, Peace and the Integrity of Creation (JPIC). Click here

[Posted

Apr 16] |

|

Sydney Alliance assembly

[Posted

Mar 27] |

The Sydney Alliance is supported by the Marist Fathers' Australian Province 'Justice Peace & Integrity of Creation' committee who will be well represented at the Assembly |

'Bridging Sydney'

Assembly of Sydney Alliance coming soon (Mar 26) Click here for details

[Posted

Mar 10] |

The CLRI (NSW) Social Justice Committee would like to acknowledge that this calendar has

been sourced and adapted from the Environmental Outreach Committee in the

Archdiocese of Washington, which in turn was adapted from Tearfund and other sources

with help from Greater Washington Interfaith Power & Light (www.GreenMyChurch.com).

|

Carbon Fast Calendar

[Posted

Ash Wednesday, Mar 05, 2014] |

Pope Francis' message for Lent 2014

Conversion of life and

the invitation to poverty

| Dear Brothers and Sisters,

As Lent draws near, I would like to offer some helpful thoughts on our path of conversion as individuals and as a community.

These insights are inspired by the words of Saint Paul: "For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that by his poverty you might become rich" (2 Cor 8:9).

The Apostle was writing to the Christians of Corinth to encourage them to be generous in helping the faithful in Jerusalem who were in need.

What do these words of Saint Paul mean for us Christians today?

What does this invitation to poverty, a life of evangelical poverty, mean to us today?

Christ’s grace

First of all, it shows us how God works. He does not reveal himself cloaked in worldly power and wealth but rather in weakness and poverty: "though He was rich, yet for your sake he became poor …".

Christ, the eternal Son of God, one with the Father in power and glory, chose to be poor; he came amongst us and drew near to each of us; he set aside his glory and emptied himself so that he could be like us in all things (cf. Phil 2:7; Heb 4:15).

God’s becoming man is a great mystery! But the reason for all this is his love, a love which is grace, generosity, a desire to draw near, a love which does not hesitate to offer itself in sacrifice for the beloved.

Charity, love, is sharing with the one we love in all things. Love makes us similar, it creates equality, it breaks down walls and eliminates distances.

God did this with us. Indeed, Jesus "worked with human hands, thought with a human mind, acted by human choice and loved with a human heart. Born of the Virgin Mary, he truly became one of us, like us in all things except sin." (Gaudium et Spes, 22).

By making himself poor, Jesus did not seek poverty for its own sake but, as Saint Paul says "that by his poverty you might become rich".

This is no mere play on words or a catch phrase. Rather, it sums up God’s logic, the logic of love, the logic of the incarnation and the cross.

God did not let our salvation drop down from heaven, like someone who gives alms from their abundance out of a sense of altruism and piety. Christ’s love is different!

When Jesus stepped into the waters of the Jordan and was baptized by John the Baptist, he did so not because he was in need of repentance, or conversion; he did it to be among people who need forgiveness, among us sinners, and to take upon himself the burden of our sins. In this way he chose to comfort us, to save us, to free us from our misery.

It is striking that the Apostle states that we were set free, not by Christ’s riches but by his poverty.

Yet Saint Paul is well aware of the "the unsearchable riches of Christ" (Eph 3:8), that he is "heir of all things" (Heb 1:2).

So what is this poverty by which Christ frees us and enriches us? It is his way of loving us, his way of being our neighbour, just as the Good Samaritan was neighbour to the man left half dead by the side of the road (cf. Lk 10:25ff).

What gives us true freedom, true salvation and true happiness is the compassion, tenderness and solidarity of his love.

Christ’s poverty which enriches us is his taking flesh and bearing our weaknesses and sins as an expression of God’s infinite mercy to us.

Christ’s poverty is the greatest treasure of all: Jesus wealth is that of his boundless confidence in God the Father, his constant trust, his desire always and only to do the Father’s will and give glory to him.

Jesus is rich in the same way as a child who feels loved and who loves its parents, without doubting their love and tenderness for an instant.

Jesus’ wealth lies in his being the Son; his unique relationship with the Father is the sovereign prerogative of this Messiah who is poor.

When Jesus asks us to take up his "yoke which is easy", he asks us to be enriched by his "poverty which is rich" and his "richness which is poor", to share his filial and fraternal Spirit, to become sons and daughters in the Son, brothers and sisters in the firstborn brother (cf. Rom 8:29).

It has been said that the only real regret lies in not being a saint (L. Bloy); we could also say that there is only one real kind of poverty: not living as children of God and brothers and sisters of Christ.

Our witness

We might think that this "way" of poverty was Jesus’ way, whereas we who come after him can save the world with the right kind of human resources.

This is not the case. In every time and place God continues to save mankind and the world through the poverty of Christ, who makes himself poor in the sacraments, in his word and in his Church, which is a people of the poor. God’s wealth passes not through our wealth, but invariably and exclusively through our personal and communal poverty, enlivened by the Spirit of Christ.

[top of next column...] |

In imitation of our Master, we Christians are called to confront the poverty of our brothers and sisters, to touch it, to make it our own and to take practical steps to alleviate it.

Destitution is not the same as poverty: destitution is poverty without faith, without support, without hope.

There are three types of destitution: material, moral and spiritual. Material destitution is what is normally called poverty, and affects those living in conditions opposed to human dignity: those who lack basic rights and needs such as food, water, hygiene, work and the opportunity to develop and grow culturally.

In response to this destitution, the Church offers her help, her diakonia, in meeting these needs and binding these wounds which disfigure the face of humanity. In the poor and outcast we see Christ’s face; by loving and helping the poor, we love and serve Christ.

Our efforts are also directed to ending violations of human dignity, discrimination and abuse in the world, for these are so often the cause of destitution.

When power, luxury and money become idols, they take priority over the need for a fair distribution of wealth.

Our consciences thus need to be converted to justice, equality, simplicity and sharing.

No less a concern is moral destitution, which consists in slavery to vice and sin.

How much pain is caused in families because one of their members – often a young person - is in thrall to alcohol, drugs, gambling or pornography!

How many people no longer see meaning in life or prospects for the future, how many have lost hope!

And how many are plunged into this destitution by unjust social conditions, by unemployment, which takes away their dignity as breadwinners, and by lack of equal access to education and health care.

In such cases, moral destitution can be considered impending suicide.

This type of destitution, which also causes financial ruin, is invariably linked to the spiritual destitution which we experience when we turn away from God and reject his love.

If we think we don’t need God who reaches out to us though Christ, because we believe we can make do on our own, we are headed for a fall. God alone can truly save and free us.

The Gospel is the real antidote to spiritual destitution: wherever we go, we are called as Christians to proclaim the liberating news that forgiveness for sins committed is possible, that God is greater than our sinfulness, that he freely loves us at all times and that we were made for communion and eternal life.

The Lord asks us to be joyous heralds of this message of mercy and hope!

It is thrilling to experience the joy of spreading this good news, sharing the treasure entrusted to us, consoling broken hearts and offering hope to our brothers and sisters experiencing darkness.

It means following and imitating Jesus, who sought out the poor and sinners as a shepherd lovingly seeks his lost sheep. In union with Jesus, we can courageously open up new paths of evangelization and human promotion.

Dear brothers and sisters, may this Lenten season find the whole Church ready to bear witness to all those who live in material, moral and spiritual destitution the Gospel message of the merciful love of God our Father, who is ready to embrace everyone in Christ.

We can so this to the extent that we imitate Christ who became poor and enriched us by his poverty.

Lent is a fitting time for self-denial; we would do well to ask ourselves what we can give up in order to help and enrich others by our own poverty.

Let us not forget that real poverty hurts: no self-denial is real without this dimension of penance. I distrust a charity that costs nothing and does not hurt.

May the Holy Spirit, through whom we are "as poor, yet making many rich; as having nothing, and yet possessing everything" (2 Cor 6:10), sustain us in our resolutions and increase our concern and responsibility for human destitution, so that we can become merciful and act with mercy. In expressing this hope,

I likewise pray that each individual member of the faithful and every Church community will undertake a fruitful Lenten journey.

I ask all of you to pray for me. May the Lord bless you and Our Lady keep you safe.

From the Vatican, Dec 26, 2013

Feast of Saint Stephen, Deacon and First Martyr

Posted: Ash Wednesday, Mar 05, 2014

|

|

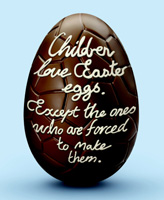

Be a good egg

Marist Sister, Noelene Simmons SM, is encouraging us to buy 'slavery-free' chocolate this Easter. In her work with Australian Catholic Religious Against Trafficking in Humans (ACRATH) Sr Noelene reports:

'In coalition with other organisations ACRATH is distributing a pamphlet encouraging the purchase of Easter chocolate that is 'slavery free'. We are deliberating using the term 'slavery free' rather than Fairtrade as there are three companies certifying cocoa – Fairtrade, UTZ certification and Rainforest Alliance. Feel free to pass the pamphlet on to whoever you wish.'

[Posted

Feb 26] |

| |

|

ACRATH's web site advises: 'Presently children as young as 12 years old are picking cocoa in West Africa to make the chocolate we eat. Some of these children are trafficked. Most are forced to pick cocoa from an early age for minimal or no wages, for long hours, in dangerous working conditions, without any possibility of attending school. Most of these children have never tasted chocolate.

'Five years ago Australian supermarkets did not have any Easter chocolate certified as slavery-free, but in 2013 there were at least six slavery-free Easter eggs and rabbits available.' |

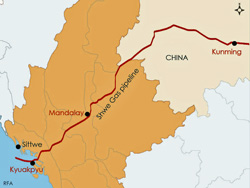

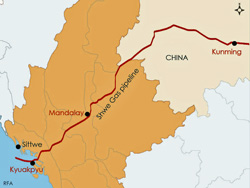

China and Myanmar's reforms

Trevor Wilson, former Australian ambassador to Myanmar, examines the important relationship with China at this time of flux...

| Background

China has long been concerned about ineffective Myanmar political, social and economic policies, many of which had direct impacts on Chinese interests, although as is customary for China, it tended to blur its public criticisms of Myanmar policies.[1]

After around 2000, in private conversations with other countries Chinese diplomatic representatives did not bother to hide their frequent frustration with the negative impacts on China from Myanmar’s poor economic management (manifested most openly in their inability to repay Chinese loans, albeit concessional loans), in striking contrast to China’s own post-1978 economic liberalisation.[2]

It is only after 1989 that China had sufficient influence in Myanmar to promote or advocate reform, or other significant policy changes, there. Yet although China had begun its own far-reaching economic reform program after 1978, on the surface it was not able to persuade Myanmar to change its ways in economic policy which could have direct, and negative, impact on China.

Ne Win’s “Burmese Way to Socialism” seemed particularly impervious to the new alternative Chinese models. If China preached the advantages of economic reform in the 1980s, there was little indication that Burma was ready to listen, and Burmese state-owned enterprises, for example, (which seem to follow an earlier Chinese economic development model) remain almost unchanged to this day.

By the end of the 1990s, Chinese officials from time to time privately and publicly revealed their dismay with Myanmar’s overall political and economic strategies which meant that China’s loans to Myanmar went unrepaid[3], that Myanmar continued to score so poorly in the UN’s human development indicators that it remained a designated least developed country, and that Myanmar’s fragile political condition magnified political risk factors for doing business in Myanmar.

In earlier years – after the mid-1990s and until around 2005 – China was openly concerned about Myanmar becoming a source of breeches of trans-national criminal activity (smuggling of people and goods, narcotics trafficking, public health epidemics).

Even in officially controlled media, during these years reports often appeared of drug traffickers being arrested and sentenced on both sides of the border. However, China found other ways to deal with these matters through their diplomacy and through regional bodies, although these approaches were rather indirect and may not have guaranteed productive outcomes.

For example, in an effort to reduce such trans-national crimes and to defuse negative impacts, regional cooperation arrangements notionally between China and ASEAN were set up for information exchanges and training. China openly supported these multilateral regional initiatives, which served its purpose of enhancing Myanmar’s capacity to conform with trans-national norms.

Outside this area, from about this time, China resorted to occasional statements expressing its concerns about these problems.

For example, China’s frequent public support for Myanmar to pursue “political stability and reconciliation” was codeword for finding some kind of rapprochement with the political opposition (a luxury China did not itself have to worry about!).

Generally, while China sought to minimise openly negative comments on Myanmar government actions (for example, its weak anti-narcotics efforts), it could be expected that Chinese representatives, in their own direct discussions with the Myanmar government, would have expressed their views fairly clearly, if politely.

But, hardly surprisingly, China never joined the public western chorus against anti-democratic practices or human right abuses by a succession of Myanmar military regimes. On some matters, especially those with a “trans-national” character, China was able to press for multilateral or regional support for additional efforts by Myanmar to reduce or eliminate infectious diseases (SRAS, HIV/AIDS), narcotics trafficking etc.

But in some regional bodies around this time, China found that Myanmar would tacitly support anti-Chinese actions (for example, criticism of China in the Mekong Commission for building dams on the upper Mekong River).

So multilateral action sometimes helpfully moved Myanmar closer to international standards, but did not always provide satisfactory outcomes for China.

[top of next column...] |

Meanwhile, China’s actual financial support for Myanmar gained China little kudos and minimal benefits: senior elements of the Burmese Army remained quite hostile towards China for historically funding their sworn enemy, the Communist Party of Burma; and among the people, latent anti-Chinese sentiment was widespread.[4]

For their part, Myanmar Governments were duly grateful for Chinese assistance, as well as Chinese political support (on UN sanctions, for example).

However, there is little or no public evidence that the Myanmar military regime modified their policies in response to expressions of Chinese concern, or requests for change. Chinese views might have coincided with those of multilateral agencies involved in assessing Myanmar economic and social policies, but China was not notable for reinforcing the views of the IMF or the World Bank or the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) which those agencies had been conveying consistently to Myanmar/Burma since the mid-1990s in some cases.

While under Myanmar’s military regime, Myanmar always seemed to be satisfied to have close cooperation with China.

However, Army officers (who occasionally intimated that they remained quite bitter about the longstanding political and military support that the Chinese Communist Party had given the Communist Party of Burma in the latter’s post-independence struggle against the Burmese State) were apparently not always happy with the quality of Chinese military cooperation.[5]

Much later, Myanmar officials were almost gleeful when around 2002 the Myanmar leadership rejected a Chinese proposal for shipping access to the Indian Ocean via the Irrawaddy River on the grounds that this violated Myanmar’s sovereignty.[6]

Until now, China has enjoyed a significant presence in Myanmar, as a donor, investor and trader, in the virtual absence of most of the traditional developed country sources of such flows.

Although China was far from satisfied with Myanmar political, economic and social policies, and often made this clear to Myanmar leaders and to others, it did not noticeably seek to use its position of influence in Myanmar between 1988 and 2008, to press for urgent policy reform. Inasmuch as, during this period, China faced limited competition or opposition in getting what it wanted in Myanmar, there was perhaps no reason for it to insist on policy changes from the Myanmar side.

Especially after China stopped assisting the Burmese Communist Party in 1989, it approached its relationship with Myanmar rather cautiously, and sought to avoid both becoming too dependent on Myanmar or allowing Myanmar to be become too dependent on China.[7] It was not until around 2005 that China decided it could increase its reliance on Myanmar as a conduit for China’s resource needs. Why did this happen then?...

(Click here for the full text and footnotes)

Posted: Feb 12, 2014

(from New Mandala, Feb 10, 2014) |

Fawlty thinking about the aftermyth of war

Ray Cassin, is a contributing consulting editor of Eureka Street, commenting as the centenary of the Great War approaches...

| 'Don't mention the war!' admonishes John Cleese in the classic television comedy series Fawlty Towers.

And of course he himself never stops mentioning the war in front of his hotel's German guests, with ever more embarrassing consequences.

It's a famously funny scene, but not only because it reveals Cleese's character, the hapless Basil Fawlty, at his bumbling worst.

It is a reminder that, although we must talk about the events, including war, that have shaped us, we can never do so with complete detachment.

To mention the war — any war — almost always ignites debate about whether it was worth fighting, however much the speaker feigns neutrality on the subject.

And sometimes, mentioning the war becomes a way of continuing to fight it.

The war that Fawlty would rather not have mentioned was the Second World War but his predicament applies equally well to the mention of its great precursor, which began in 1914.

As the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War approaches (variously in July or August, depending on which of the belligerent states is being discussed), we shall be deluged with mentions of it, and they will not stop when the clocks click past midnight on 31 December.

The deluge will last at least until the centenary of the armistice on 11 November 2018, and will probably extend beyond that to the centenaries of the peace conferences — there were several, not just the best-known at Versailles — that began in 1919.

For Australians, mentions of war will probably flow thickest and fastest next year, with the centenary of the Gallipoli landings on 25 April, a date that for many has become the de facto national day.

And beyond that there are other significant anniversaries we shall not be allowed to forget, most notably those of the great slaughterhouse battles on the Western Front, such as the Somme (1916) and Passchendaele (1917).

Mentioners who want to remind us that the war of 1914–18 was indeed a global conflict, not only the Anglo-German one familiar from popular culture, will also cite other slaughterhouses such as Tannenberg (1914), Verdun (1916) and Caporetto (1917).

They will note that the modern Middle East with its discontents was created by the Allied dismemberment of the Ottoman empire, and that the map of modern Europe is a consequence of the collapse of the Habsburg, Hohenzollern and Romanov monarchies.

They will trace the decline of imperial Britain to the staggering cost of victory, and the end of European ascendancy to the presence of Japan among the victors and, above all, to the US entry into the war.

Yes, for most of the decade ahead the war buffs will be in overdrive. We shan't escape them, nor should we try.

What matters is which lot of buffs seize control of the public narrative, and thereby of the collective understanding of the war's significance.

There will be a swag of popular histories — indeed, they have already begun to appear — with titles like The Year the World Ended (1914, according to the author of that work, Paul Ham).

Most of these will follow a formula publishers know to be successful, as the well-stocked shelves of military history in bookshops testify.

[top of next column...] |

They will mostly focus on particular battles or campaigns, and will extol the courage and resilience of ordinary soldiers.

With varying degrees of enthusiasm and overtness, these books will feed from, and nourish further, conceptions of national identity as having been forged by the experience of war.

The Gallipoli anniversary will be a magnet for accounts of this kind. Most will not be sufficiently critical of received views to ask why a nation that, uniquely among the world's democracies, united itself by peaceful negotiation has since chosen to regard Federation as a lesser achievement than the waste of its youth in an imperial military adventure abroad.

There will be works of academic history, too, addressed to the general reader as well as to professional peers.

One well-reviewed example, Joan Beaumont's Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War, has already appeared.

These works will raise critical questions that the popular histories shun and, like Beaumont's work, they will focus on the home front and its debates about the war as well as on the military action.

Some of the academic historians, like Clare Wright in her article 'A Splendid Object Lesson', to be published later this year in theJournal of Women's History, will vigorously take issue with the militarisation of national identity in the Anzac legend.

And as their arguments gain media coverage the critics of the legend, and of received views of the First World War generally, will become targets for politicians, shock-jocks and bully-pulpit columnists.

As the real war recedes into an imagined past, the history wars are starting all over again.

The politicians have already fired the first shots, predictably directed at the teaching of history in school curricula. Britain's education secretary, Michael Gove, has complained about the portrayal of the First World War in satirical films such as Oh! What a Lovely War and television series such as Blackadder Goes Forth.

Their emphasis on incompetent generals, conniving politicians and mass slaughter, Gove says, has distracted from the sense that the war was a just crusade against German militarism.

Meanwhile, out here in what used be the Antipodean colonies, the Government has taken its cue from Westminster, as it did in 1914. Federal Education Minister Christopher Pyne has said he hopes a renewed emphasis on Anzac Day will result from the review of the history curriculum that is underway.

As the anniversaries are reached, one by one, during the next four years, many people will wish, Fawlty-like, that the war had not been mentioned.

Or they might find themselves saying with Fawlty: 'I mentioned it once, but I think it's all right.' It will never be all right, Basil.

The dead are too many. But we still owe them a debt, which we should repay by confronting the legends, the aftermyth of war, with the truth.

Posted: Feb 06, 2014

(from Eureka Street, Jan, 2014) |

Celebrating diversity on Australia Day

Andrew Hamilton, consulting editor of Eureka Street, makes this timely comment on how we handle Australian identity...

| Next week begins with Australia Day and ends with the Chinese New Year.

The juxtaposition suggests pertinent questions about Australian identity, especially the ways in which Australians have alternately included and excluded those seen as outsiders.

This is most evident in the relationship between Australian settlers' attitudes to Indigenous Australians, but it is also seen in Australian attitudes to Chinese and other Asian peoples.

Chinese people first came to Australia in considerable numbers during the Gold Rush, and for a time formed up to seven per cent of the population.

They came first as miners, and later supported themselves by farming and small business.

From the beginning their position was precarious. The colonies passed laws to exclude Asian immigration; on the gold fields there were anti-Chinese riots.

The grounds of hostility lay in their virtues, not their vices: they worked so hard and were so thrifty that others found them difficult to compete with.

After Federation, hostility found expression in the White Australia policy.

It was based on the threat posed by cheap imported labour to Australian workers but also reflected the belief that the Chinese and other races were inferior. In speaking to the 1901 immigration restriction bill Edmund Barton, the first Australian prime minister, was explicit on this point:

I do not think (either) that the doctrine of the equality of man was really ever intended to include racial equality. There is no racial equality.

[top of next column...] |

There is basic inequality. These races are, in comparison with white races — I think no one wants convincing of this fact — unequal and inferior.

The doctrine of the equality of man was never intended to apply to the equality of the Englishman and the Chinaman.

There is deep-set difference, and we see no prospect and no promise of its ever being effaced.

Nothing in this world can put these two races upon an equality. Nothing we can do by cultivation, by refinement, or by anything else will make some races equal to others.

British opposition to measures that would inflame its relationship with its colonies deterred the legislators from explicitly excluding immigrants on the grounds of race.

But the dictation test provided a genteel mechanism for exclusion, the forerunner of such smarmy devices as the exclusion of the Australian mainland from the immigration zone.

In the 1960s the policy of exclusion changed to one of inclusion as Australians began to realise that their prosperity depended on building good relationships with their Asian neighbours.

The abolition of the White Australia Policy and the later grant of citizenship to Chinese students after the Tiananmen Square massacre established complex circular patterns of immigration and belonging.

Chinese migrated to Australia, established citizenship and residence and then returned to China, sending their children in turn to study and gain residence.

Posted: Jan 26, 2014

(from Eureka Street, Jan 22, 2014) |

|

.jpg)